[LINQ via C# series]

[Category Theory via C# series]

Latest version: https://weblogs.asp.net/dixin/category-theory-via-csharp-3-functor-and-linq-to-functors

Functor and functor laws

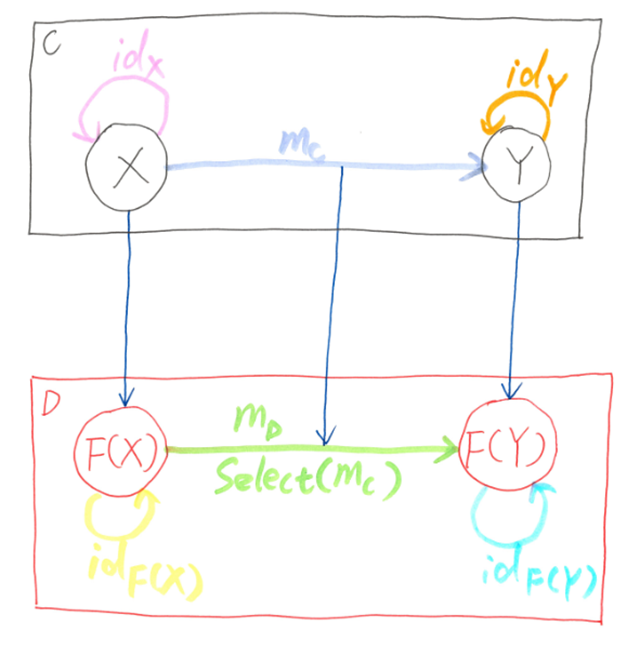

A functor F: C → D is a structure-preserving mapping from category C to category D:

As above diagram represented, F:

- maps objects X, Y ∈ ob(C) to objects F(X), F(Y) ∈ ob(D)

- also maps morphism mC: X → Y ∈ hom(C) to a new morphism mD: F(X) → F(Y) ∈ hom(D)

- To align to C#/.NET terms, this mapping ability of functor will be called “select” instead of “map”. That is, F selects mC to mD .

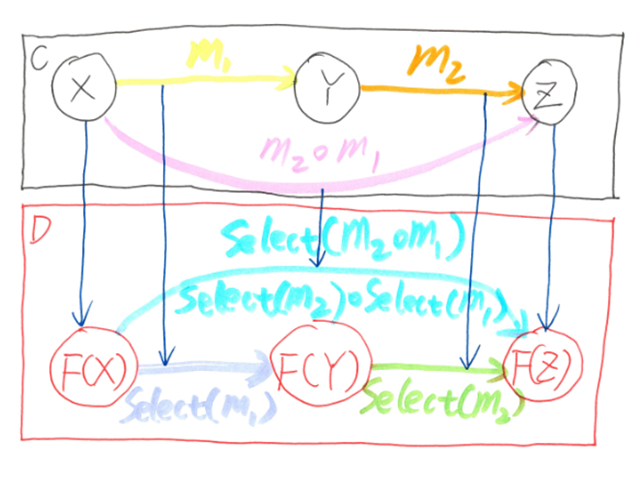

and satisfies the functor laws:

So the general functor should be like:

// Cannot be compiled.public interface IFunctor<in TSourceCategory, out TTargetCategory, TFunctor<>> where TSourceCategory : ICategory<TSourceCategory> where TTargetCategory : ICategory<TTargetCategory> where TFunctor<> : IFunctor<TSourceCategory, TTargetCategory, TFunctor<>>{ IMorphism<TFunctor<TSource>, TFunctor<TResult>, TTargetCategory> Select<TSource, TResult>( IMorphism<TSource, TResult, TSourceCategory> selector);}A TFunctor<>, which implements IFunctor<…> interface, should have a method Select, which takes a morphism from TSource to TResult in TFromCategory, and returns a morphism from TFunctor

C#/.NET functors

A C# functor can select (maps) a morphism in DotNet category to another morphism still in DotNet category, such functor maps from a category to itself is called endofunctor.

Endofunctor

A endofunctor can be defined as:

// Cannot be compiled.public interface IEndofunctor<TCategory, TEndofunctor<>> : IFunctor<TCategory, TCategory, TEndofunctor<>> where TCategory : ICategory<TCategory> where TEndofunctor<> : IFunctor<TEndofunctor, TEndofunctor<>>{ IMorphism<TEndofunctor<TSource>, TEndofunctor<TResult>, TCategory> Select<TSource, TResult>( IMorphism<TSource, TResult, TCategory> selector);}So an endofunctor in DotNet category, e.g. EnumerableFunctor

// Cannot be compiled.// EnumerableFunctor<>: DotNet -> DotNetpublic class EnumerableFunctor<T> : IFunctor<DotNet, DotNet, EnumerableFunctor<>>{ public IMorphism<EnumerableFunctor<TSource>, EnumerableFunctor<TResult>, DotNet> Select<TSource, TResult>( IMorphism<TSource, TResult, DotNet> selector) { // ... }}Unfortunately, all the above code cannot be compiled, because C# does not support higher-kinded polymorphism. This is actually the biggest challenge of explaining category theory in C#.

Kind issue of C# language/CLR

Kind is the (meta) type of a type. In another word, a type’s kind is like a function’s type. For example:

- int’s kind is *, where * can be read as a concrete type or closed type. This is like function (() => 0)’s type is Func

. - IEnumerable

is a closed type, its kind is also *. - IEnumerable<> is a open type, its kind is * → *, which can be read as taking a closed type (e.g. int) and constructs another closed type (IEnumerable

). This is like function ((int x) => x)’s type is Func<int, int>. - In above IFunctor<TFromCategory, TToCategory, TFunctor<>> definition, its type parameter TFunctor<> has a kind * → *, which makes IFunctor<TFromCategory, TToCategory, TFunctor<>> having a higher order kind: * → * → (* → *) → *. This is like a function become a higher order function if its parameter is a function.

Unfortunately, C# does not support type with higher order kind. As Erik Meijer mentioned in this video, the reasons are:

- CLR does not support higher order kind

- Supporting higher order kind causes more kind issues. For example, IDictionary<,> is a IEnumerble<>, but they have different kinds: * → * → * vs. * → *.

So, instead of higher-kinded polymorphism, C# recognizes the functor pattern of each functor, which will be demonstrated by following code.

The built-in IEnumerable<> functor

IEnumerable

public static IMorphism<IEnumerable<TSource>, IEnumerable<TResult>, DotNet> Select<TSource, TResult>( IMorphism<TSource, TResult, DotNet> selector){ // ...}IEnumerable

Second, in DotNet category, morphisms are functions. That is, IMorphism<TSouece, TResult, DotNet> and Func<TSouece, TResult> can convert to each other. So above select/map is equivalent to:

// Select = selector -> (source => result)public static Func<IEnumerable<TSource>, IEnumerable<TResult>> Select<TSource, TResult>( Func<TSource, TResult> selector){ // ...}Now Select’s type is Func<T1, Func<T2, TResult>>, so it is a curried function. It can be uncurried to a equivalent Func<T1, T2, TResult>:

// Select = (selector, source) -> resultpublic static IEnumerable<TResult> Select<TSource, TResult>( // Uncurried Func<TSource, TResult> selector, IEnumerable<TSource> source){ // ...}The positions of 2 parameters can be swapped:

// Select = (source, selector) -> resultpublic static IEnumerable<TResult> Select<TSource, TResult>( // Parameter swapped IEnumerable<TSource> source, Func<TSource, TResult> selector){ // ...}The final step is to make Select an extension method by adding a this keyword:

// Select = (this source, selector) -> resultpublic static IEnumerable<TResult> Select<TSource, TResult>( // Extension method this IEnumerable<TSource> source, Func<TSource, TResult> selector){ // ...}which is just a syntactic sugar and does not change anything. The above transformation shows:

- In DotNet category, IEnumerable<>’s functoriality is equivalent to a simple familiar extension method Select

- If the last Select version above can be implemented, then IEnumerable

is a functor.

IEnumerable

[Pure]public static partial class EnumerableExtensions{ // C# specific functor pattern. public static IEnumerable<TResult> Select<TSource, TResult>( // Extension this IEnumerable<TSource> source, Func<TSource, TResult> selector) { foreach (TSource item in source) { yield return selector(item); } }

// General abstract functor definition of IEnumerable<>: DotNet -> DotNet. public static IMorphism<IEnumerable<TSource>, IEnumerable<TResult>, DotNet> Select<TSource, TResult> (this IMorphism<TSource, TResult, DotNet> selector) => new DotNetMorphism<IEnumerable<TSource>, IEnumerable<TResult>>( source => source.Select(selector.Invoke));}So IEnumerable

Functor pattern of LINQ

Generally in C#, if a type F

- have a instance method or extension method Select, taking a Func<TSource, TResult> parameter and returning a F

then:

- F<> is an endofunctor F<>: DotNet → DotNet

- F<> maps objects TSource, TResult ∈ ob(DotNet) to objects F

, F ∈ ob(DotNet) - F<> also selects morphism selector : TSource → TResult ∈ hom(DotNet) to new morphism : F

→ F ∈ hom(DotNet)

- F<> maps objects TSource, TResult ∈ ob(DotNet) to objects F

- F<> is a C# functor, its Select method can be recognized by C# compiler, so the LINQ syntax can be used:

IEnumerable<int> enumerableFunctor = Enumerable.Range(0, 3);IEnumerable<int> query = from x in enumerableFunctor select x + 1;which is compiled to:

IEnumerable<int> enumerableFunctor = Enumerable.Range(0, 3);Func<int, int> addOne = x => x + 1;IEnumerable<int> query = enumerableFunctor.Select(addOne);IEnumerable<>, functor laws, and unit tests

To test IEnumerable<> with the functor laws, some helper functions can be created for shorter code:

[Pure]public static class MorphismExtensions{ public static IMorphism<TSource, TResult, DotNet> o<TSource, TMiddle, TResult>( this IMorphism<TMiddle, TResult, DotNet> m2, IMorphism<TSource, TMiddle, DotNet> m1) { Contract.Requires(m2.Category == m1.Category, "m2 and m1 are not in the same category.");

return m1.Category.o(m2, m1); }

public static IMorphism<TSource, TResult, DotNet> DotNetMorphism<TSource, TResult> (this Func<TSource, TResult> function) => new DotNetMorphism<TSource, TResult>(function);}The above extension methods are created to use ∘ as infix operator instead of prefix, for fluent coding, and to convert a C# function to a morphism in DotNet category.

And an Id helper function can make code shorter:

[Pure]public static partial class Functions{ // Id is alias of DotNet.Category.Id().Invoke public static T Id<T> (T value) => DotNet.Category.Id<T>().Invoke(value);}Finally, an assertion method for IEnumerable

// Impure.public static class EnumerableAssert{ public static void AreEqual<T>(IEnumerable<T> expected, IEnumerable<T> actual) { Assert.IsTrue(expected.SequenceEqual(actual)); }}The following is the tests for IEnumerable

[TestClass()]public partial class FunctorTests{ [TestMethod()] public void EnumerableGeneralTest() { IEnumerable<int> functor = new int[] { 0, 1, 2 }; Func<int, int> addOne = x => x + 1;

// Functor law 1: F.Select(Id) == Id(F) EnumerableAssert.AreEqual(functor.Select(Functions.Id), Functions.Id(functor)); // Functor law 2: F.Select(f2.o(f1)) == F.Select(f1).Select(f2) Func<int, string> addTwo = x => (x + 2).ToString(CultureInfo.InvariantCulture); IMorphism<int, int, DotNet> addOneMorphism = addOne.DotNetMorphism(); IMorphism<int, string, DotNet> addTwoMorphism = addTwo.DotNetMorphism(); EnumerableAssert.AreEqual( addTwoMorphism.o(addOneMorphism).Select().Invoke(functor), addTwoMorphism.Select().o(addOneMorphism.Select()).Invoke(functor)); }}And the following is the tests for IEnumerable

public partial class FunctorTests{ [TestMethod()] public void EnumerableCSharpTest() { bool isExecuted1 = false; IEnumerable<int> enumerable = new int[] { 0, 1, 2 }; Func<int, int> f1 = x => { isExecuted1 = true; return x + 1; };

IEnumerable<int> query1 = from x in enumerable select f1(x); Assert.IsFalse(isExecuted1); // Laziness.

EnumerableAssert.AreEqual(new int[] { 1, 2, 3 }, query1); // Execution. Assert.IsTrue(isExecuted1);

// Functor law 1: F.Select(Id) == Id(F) EnumerableAssert.AreEqual(enumerable.Select(Functions.Id), Functions.Id(enumerable)); // Functor law 2: F.Select(f2.o(f1)) == F.Select(f1).Select(f2) Func<int, string> f2 = x => (x + 2).ToString(CultureInfo.InvariantCulture); EnumerableAssert.AreEqual( enumerable.Select(f2.o(f1)), enumerable.Select(f1).Select(f2)); // Functor law 2: F.Select(f2.o(f1)) == F.Select(f1).Select(f2) EnumerableAssert.AreEqual( from x in enumerable select f2.o(f1)(x), from y in (from x in enumerable select f1(x)) select f2(y)); }}IEnumerable<> is like the List functor in Haskell.